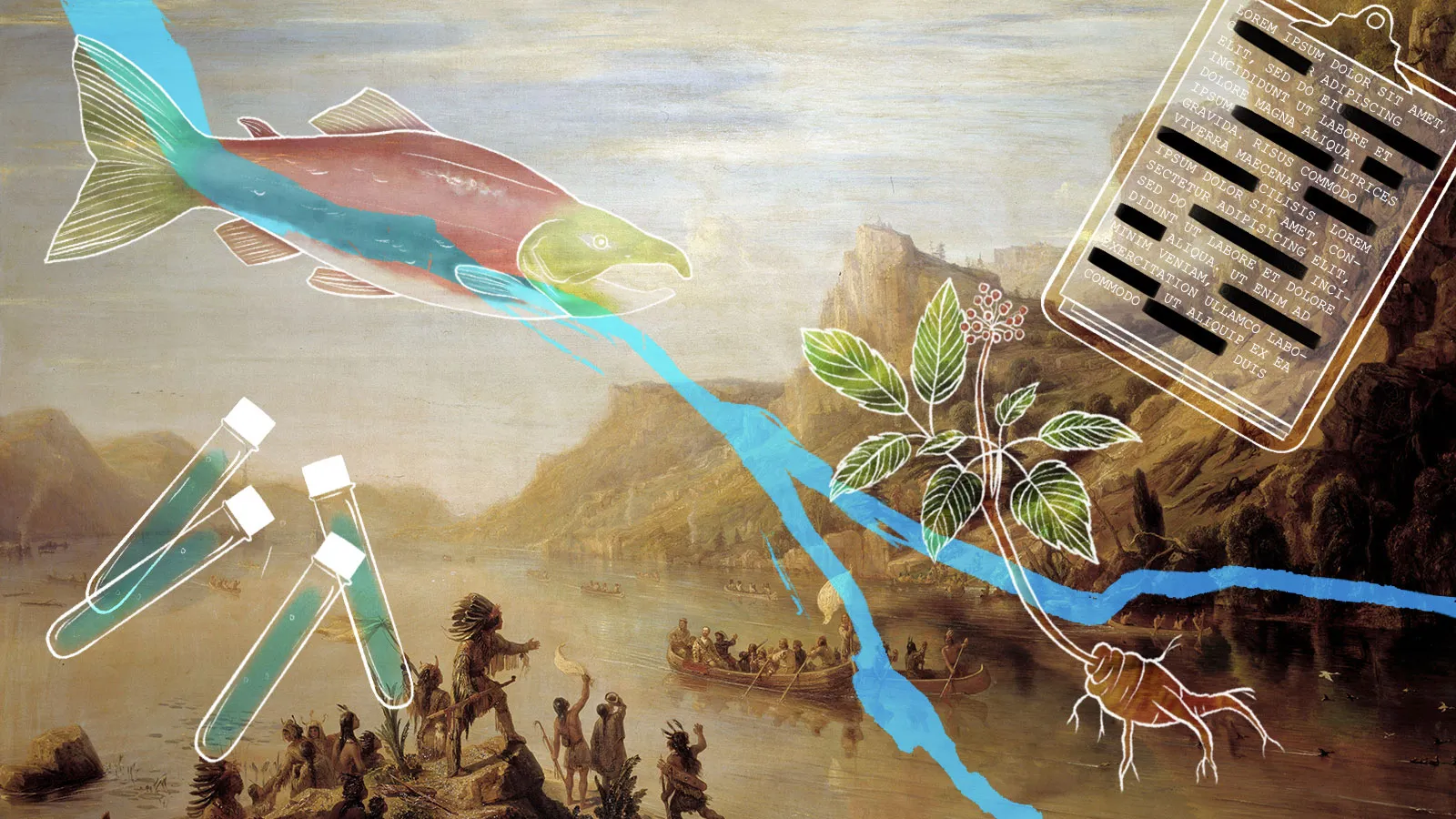

Across the world, Indigenous communities have long practiced ways of living that harmonize with nature’s cycles. Their knowledge systems—rooted in observation, spirituality, and sustainable interaction—offer crucial insights into addressing today’s climate challenges. While modern science often relies on technology and data, Indigenous wisdom emphasizes balance, respect, and coexistence with the Earth. As the effects of global warming intensify, integrating Indigenous knowledge into climate solutions has become both a moral and practical necessity.

The Deep Connection Between Indigenous People and Nature

Indigenous cultures view the environment not as a resource to be exploited but as a living system with which humans share a relationship of respect and reciprocity. This worldview is central to many Indigenous traditions, such as the Native American concept of “Mother Earth” and the Australian Aboriginal belief in “Country” — a spiritual, cultural, and ecological bond with the land. This deep-rooted connection fosters long-term thinking and ensures that natural systems are cared for across generations. Such perspectives contrast sharply with short-term industrial models that have driven much of modern environmental degradation.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge: A Scientific Foundation

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) refers to the cumulative understanding Indigenous peoples hold about their environment, gained through observation, experience, and oral transmission. TEK encompasses knowledge of weather patterns, soil fertility, plant medicine, animal behavior, and resource management. For example, Inuit communities in the Arctic use generations of knowledge about ice formation and animal migration to navigate and predict environmental changes—information now being integrated into climate research. By combining TEK with modern science, policymakers and researchers can develop more adaptive and locally informed climate solutions.

Land Management and Fire Control Practices

One of the most striking examples of Indigenous climate adaptation is traditional fire management. Aboriginal Australians have practiced “cool burning” for thousands of years—setting small, controlled fires to clear underbrush, promote new plant growth, and prevent catastrophic wildfires. Similar methods exist among Native American tribes in California and Indigenous groups in South America. These practices maintain ecosystem health, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and protect biodiversity. Today, environmental agencies are reintroducing these methods to mitigate the destructive wildfires caused by climate change and poor land management.

Water Conservation and Sustainable Agriculture

Indigenous communities have developed sophisticated water management systems perfectly adapted to local climates. The Subak irrigation system in Bali, governed by temple networks, ensures equitable water sharing and sustainable farming. In the Andes, Quechua and Aymara people built intricate terraces and canals that conserved soil moisture and prevented erosion—techniques that remain relevant in modern climate adaptation programs. African Indigenous farmers use intercropping and rotational grazing to preserve soil fertility and reduce drought impact. These time-tested strategies highlight how local knowledge can offer practical models for modern agriculture facing water scarcity.

Table: Indigenous Knowledge and Its Climate Contributions

| Region/Culture | Practice | Climate Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal Australians | Controlled “cool burning” | Reduces wildfire risk and maintains biodiversity |

| Andean Farmers | Terraced agriculture and water channels | Prevents soil erosion and conserves water |

| Inuit Communities | Seasonal ice and wildlife monitoring | Supports climate prediction and adaptation |

| Pacific Islanders | Traditional reef management | Protects marine ecosystems and food security |

| African Pastoralists | Rotational grazing | Restores soil and prevents desertification |

Protecting Forests Through Indigenous Stewardship

Indigenous peoples manage nearly a quarter of the world’s land surface, including many of its most biodiverse regions. Forests governed by Indigenous communities are often healthier and store more carbon than those under commercial management. In the Amazon Basin, Indigenous tribes protect millions of hectares of rainforest from deforestation by monitoring illegal logging and practicing sustainable harvesting. In North America, tribal reforestation projects restore native tree species and improve carbon sequestration. Recognizing Indigenous land rights is therefore one of the most effective strategies for reducing global carbon emissions and preserving biodiversity.

Ocean and Coastal Knowledge for Climate Resilience

Island and coastal Indigenous groups have developed deep knowledge of marine ecosystems. Pacific Islanders use traditional navigation and reef management techniques that sustain fish populations and protect coral reefs from overuse. The Hawaiian kapu system, which restricts fishing during breeding seasons, has been revived as a model for marine conservation. These local systems promote ecological balance and strengthen communities’ ability to adapt to rising sea levels and ocean acidification. Integrating such wisdom into global coastal management programs enhances both environmental and cultural resilience.

Indigenous Climate Activism and Policy Influence

In recent years, Indigenous leaders have become global voices for climate justice. From Greta Thunberg’s allies among Sámi reindeer herders to Amazonian activists defending rainforests, Indigenous representatives emphasize that climate solutions must include social and cultural equity. The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) now acknowledges Indigenous knowledge as essential for adaptation and mitigation. Projects that combine community-driven stewardship with scientific research—such as Canada’s First Nations Guardians programs—demonstrate how collaboration can yield powerful results.

Challenges in Integrating Indigenous Knowledge

Despite its value, Indigenous knowledge is often overlooked or undervalued in formal climate policies. Many Indigenous territories face threats from deforestation, mining, and forced displacement. Additionally, traditional knowledge systems are transmitted orally, making them vulnerable to loss as younger generations migrate to urban areas. True climate partnership requires not only technical integration but also respect for Indigenous sovereignty, intellectual property, and cultural rights. Recognizing Indigenous peoples as equal partners, rather than beneficiaries, is key to ensuring that traditional wisdom informs sustainable futures.

The Path Forward: Blending Knowledge for a Sustainable Future

The integration of Indigenous knowledge and modern science represents one of the most promising paths toward solving the climate crisis. This collaboration must be built on trust, cultural respect, and shared decision-making. Scientists are increasingly turning to Indigenous communities for insights into carbon capture, biodiversity restoration, and ecosystem resilience. For instance, projects in Canada and Australia have shown that co-management of natural resources—where Indigenous and scientific systems work together—leads to better environmental and social outcomes. When ancient wisdom meets modern innovation, humanity gains a holistic toolkit for protecting the planet.

FAQs

1. How does Indigenous knowledge help in combating climate change?

Indigenous knowledge provides adaptive, location-specific strategies for managing resources, predicting climate shifts, and protecting ecosystems. It offers sustainable practices that complement scientific methods and promote resilience.

2. Why should Indigenous communities be included in climate policymaking?

Indigenous peoples are the custodians of vast ecosystems and possess generations of ecological insight. Including them ensures that climate solutions are culturally appropriate, ethical, and effective at local and global levels.

3. What can modern science learn from Indigenous traditions?

Modern science can learn to value interconnectedness, long-term stewardship, and community-based decision-making. These principles help create sustainable solutions rooted in respect for both people and the planet.